The soot, ruin, and lunacy required to outpace extinction

The last few years have introduced us to a new breed of radical green cults—people so disenchanted with humanity that they dream of rolling us all back into some pre-industrial mud hut existence. Not content with guilt-tripping you over your plastic straw, they flirt openly with the fantasy of a post-human Earth. One would be forgiven for thinking their true dream is a planet uninhabited, left to the wolves, the moss, and the beetles. If only we disappeared, they sigh, Earth could finally heal.

You’ve heard the sermons. They talk as if the planet were a giant mother-goddess with a thermostat and a grudge. A sentient entity keeping everything in divine equilibrium. A Gaia. Or, to update the myth with a Hollywood gloss, the planet as Ewa, the glowing blue jellyfish deity from Avatar, orchestrating a hive-mind dictatorship where all creatures submit to the Great Balance. A nice bedtime story for children and cultists alike.

But reality? Nature isn’t a benevolent mother nor a stern goddess. It’s a feral drunk stumbling through eons with a baseball bat, randomly smashing species off the stage. Chaos, not balance, is her method. She has tried to erase life more times than your high-school math teacher erased your scribbles. Asteroids have hammered continents into molten slag. Volcanoes have dimmed the sun for decades at a time, choking biospheres. Plagues have scythed through forests and herds and dynasties alike. Whole branches of the tree of life ended not with a whimper but a geological thud. Nature has never once aspired to “balance.” If she has a personality, it’s that of an arsonist in a fireworks factory.

This post first appeared in 2020, back when I still entertained hope that rational arguments might sway public sentiment. I’ve since remastered it—sharpened the edges, clarified the threat, and realigned it with the Grimwright ethos: use what works, discard the rest, and always—always—question the narrative. The date remains unchanged as a historical marker. The content does not.

Of course, try explaining that to an extremist. Their relationship to facts is about as tender as Torquemada’s with heretics. They don’t want truth; they want feelings. And feelings have a nasty historical habit of being directed at unwanted people. When ideologues want balance, they usually mean subtraction.

History is littered with subtraction exercises. The unwanted are always shipped somewhere, enslaved, buried, or simply wished out of existence. Entire continents—the Americas, Australia—were colonized not only by adventurers but by Europe’s rejects, exiles, debtors, zealots, and dreamers who decided someone else’s land looked greener. The unwanted became pioneers. Persecuted Huguenots, Puritans, Jews, Armenians—the names vary, the rhythm is the same. Flee persecution, find new land, start over, rinse and repeat.

Even collapsing Rome knew the story. As the empire wheezed into decline, wave after wave of whole peoples rolled across Europe, reshaping it in their search for safety, food, or simply less marauding neighbors. Migration wasn’t a “problem”; it was the weather. And today? We’re not done. Only the tribes have changed uniforms. The “digital nomad” with his laptop in Bali is cousin to the Gothic tribe wandering across the Danube. They’re both chasing a frontier.

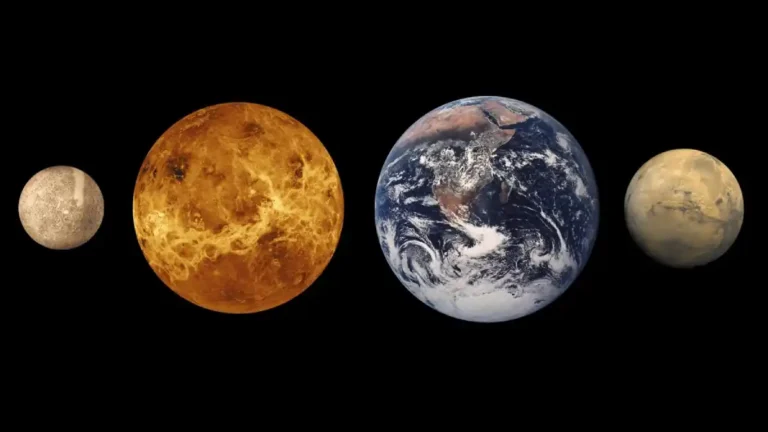

Frontiers of land are running short, but frontiers of the mind and of space? Those are still wide open. And here I confess: the doomsayers are half-right. Humanity must eventually leave this planet. Not because Gaia is going to throw us out like an unruly tenant, but because civilizations build pressure. They grow fat, bored, decadent, and brittle. They stagnate unless forced to leap. A frontier is a release valve. A new world demands new skills, new daring, new mistakes. That friction is evolution.

Too far-fetched? Perhaps. But remember, Columbus seemed mad to his peers. A short route to India by going west? Sure, pull the other one. Yet from his foolish ambition came consequences so vast they’re still reshaping the world. Human history lurches forward not because committees planned it, but because some lunatic insisted on trying something everyone else laughed at.

Last Saturday gave us another of those lunatic moments. Humanity, courtesy of SpaceX, shoved another manned rocket into orbit to rendezvous with the International Space Station. Nothing new? Perhaps—after all, people have been climbing into tin cans and lighting the fuse for more than half a century. But here’s the twist: this one wasn’t a government stunt. It was built, launched, and landed by a private company. That matters. Because space has ceased to be a taxpayer-funded prestige project and become a business.

And businesses don’t survive on glory. They require reliability, repeatability, and profit. The Cold War space race, in retrospect, was a fever dream of reckless spending. Rockets were treated like champagne bottles—smashed for one celebratory moment and then discarded. Every launch left behind a carcass of metal sinking into the ocean. The Shuttle tried to solve this with reusability, but managed instead to become a budgetary black hole. Each refurbishment cost more than building a new rocket from scratch. Economics never mattered, only the size of the national ego.

Enter Musk and Bezos, our new robber barons of the stratosphere. Say what you will about their egos—at least they’re in it for more than a flag-waving photo-op. They looked at space not as a dick-measuring contest but as an industry. Rockets that can land on their tails like something out of a 1970s comic book suddenly became real. I remember staring at pulp illustrations of rockets descending vertically and thinking: nonsense, childish fantasy. Yet here we are, jaws slack, watching a Falcon booster land on a drone ship as if Wernher von Braun’s doodles had been given life.

Still, don’t be fooled into thinking rockets are now like airplanes, ready for a quick refuel, a sweep of the cabin, and a fresh set of pretzels. No—each Falcon still requires major surgery between launches. The engines, coated in soot and carbon sediment, demand laborious overhaul. Reusability is relative: it’s less wasteful than throwing the whole machine into the sea, but it’s still a long way from true turnaround.

And here lies the conundrum. Space travel is ruinously expensive because our engines are finicky, our fuels dirty or dangerous, and our designs tailored to stages of flight like fragile prima ballerinas. If rockets are to become as common as airplanes, we need a revolution not only in reusability but in propulsion itself.

A rocket engine is, in essence, glorified plumbing. A steel tube pumps fuel and oxidizer into a chamber where combustion occurs at pressures that would turn a tank into tinfoil. Exhaust gases roar out the nozzle, pushing the rocket upward through Newton’s revenge. But unlike jet engines, rockets cannot sip oxygen from the air—they must carry their own oxidizer, usually liquid oxygen (LOX). This means enormous cryogenic tanks and pumps powerful enough to terrify an oil rig.

The choice of fuel is everything. Two titans dominate: RP-1, a highly refined kerosene, and LH₂, liquid hydrogen cooled to temperatures that make Antarctica look tropical. RP-1 is dense, cheap, and perfect for the first punch through the thick soup of atmosphere. But it burns dirty, leaving soot and oxides that foul engines and limit reuse. Hydrogen burns clean, efficient, and perfect for vacuum stages—but is hellishly difficult to store, leaks like a sieve, and corrodes whatever touches it.

So we mix and match. Kerosene to leave the ground, hydrogen to dance in space. But this ballet of fuels means multiple engine designs, complicated logistics, and staggering costs. It’s as if every time you wanted to fly from New York to Tokyo, you had to switch planes midair because the engines couldn’t handle both takeoff and cruising. Inefficient to the point of madness.

This, then, is why humanity still tiptoes at the edge of the cosmic ocean instead of striding across it. Our machines are too delicate, our fuels too dirty or too volatile, and our ambitions too prone to bureaucratic strangulation. We are still shackled by nature’s indifference, still building cathedrals of fire that collapse into scrap after a few glorious minutes.

But here’s the thing: despite all the mess, despite the radicals praying for our extinction and the bean-counters whining about costs, humanity keeps reaching. We are too restless to sit still. Nature may be chaos incarnate, but we are the animal that dares to wrestle with chaos, to strap ourselves atop bombs and light the fuse, hoping to touch the stars.

And that is precisely why we won’t stop. The frontier is not an option. It is our only antidote to stagnation, our only answer to the nihilistic cult that preaches mankind’s disappearance as salvation. The green radicals want subtraction; the explorers want multiplication. One path ends in silence, the other in constellations of fire.

If history has taught us anything, it is this: the unwanted, the foolish, the reckless are the ones who redefine the map. The pilgrims, the nomads, the visionaries—derided in their day, vindicated in hindsight. Columbus sailed into mockery. The Wright brothers tinkered in obscurity. Musk and Bezos may look like Bond villains today, but if humanity ever plants crops under another sun, it will be because someone like them kept throwing metal skyward until one of those contraptions worked reliably enough to become ordinary.

Nature is not our mother. She is our executioner and our midwife, delivering us into peril and possibility alike. The radicals who worship her would see us retreat into huts, gnawing on roots while congratulating ourselves on our “balance.” But balance is death. Stasis is extinction. The only way to survive chaos is to outpace it, to evolve faster than the next asteroid, the next plague, the next volcanic tantrum.

And for that, we need rockets. Dirty, finicky, gloriously explosive rockets. Engines screaming against gravity, stages falling into the sea, boosters blackened with soot, and crews strapped in with fingers crossed. A mad, dangerous, magnificent gamble—because anything less is surrender.

Next week, we’ll talk about fuels that might finally burn clean, engines that might finally endure, and whether humanity can finally stop treating space like a luxury cruise and start treating it like what it must become: home.