Heat, Humor, and the Cult of the Hottest Day Ever

I was eighteen when Robin Williams roared into my life, all manic laughter and machine-gun wit, with Good Morning Vietnam. Overnight, he wasn’t just a comedian anymore—he was a comet. An instant fixture, burned into the cortex of anyone who’d ever fumbled a VHS tape into the hungry maw of a clunky player. Yes, children, VHS: a brick of plastic with a magnetic ribbon that stored movies the way amber traps mosquitos. You had to physically fetch it, like a peasant hauling water from the well. No streaming, no instant gratification. Only rewinding—an ancient ritual involving patience, thumb blisters, and a deep suspicion that the tape might finally snap on your tenth replay.

I replayed certain scenes endlessly. One in particular lodged itself into my head like shrapnel: Adrian Cronauer bantering with a fictional soldier named Roosevelt E. Roosevelt about the weather. Not politics, not tactics, not strategy—just the suffocating, skin-melting, soul-cooking weather.

The exchange is still tattooed on my memory:

“What’s the weather like out there?”

“It’s hot! Damn hot! Real hot! Hottest thing’s my shorts. I could cook things in it. A little crotch-pot cooking.”

This post first appeared in 2019, back when I still entertained hope that rational arguments might sway public sentiment. I’ve since remastered it—sharpened the edges, clarified the threat, and realigned it with the Grimwright ethos: use what works, discard the rest, and always—always—question the narrative. The date remains unchanged as a historical marker. The content does not.

And on it spiraled, absurd and unforgettable—robes bursting into flame, heat that felt like the sun itself had taken a dump in the jungle, the desperate gallows humor of people trapped in a hellscape.

Robin Williams didn’t explain the weather. He made you feel it. The sweat prickling under your arms, the humidity slithering down your back, the sense that underwear had suddenly become a personal torture device. He turned a thermometer into theater. War became a backdrop for a laugh, an exhalation in the middle of carnage.

And maybe, just maybe, that’s what we’re missing now. Because if there was ever a time we needed humor to cut through hysteria, it’s this era of “hottest day ever” headlines.

War Correspondents of the Weather Channel

You’ve probably noticed the blitzkrieg of declarations: “Hottest day in three months,” “Hottest day since records began,” “Hottest day of all human history, forever and ever, amen.” The climate industry shouts as if Satan himself had booked a summer holiday in Seville and left the oven door open.

The frequency is relentless—daily records, weekly records, broken thermometers, shattered charts. It’s as if they discovered you can whip people into hysteria faster with Celsius than with tanks.

But before we all immolate ourselves in the Church of Carbon Sin, maybe we should pause and ask a question so naive it’s almost heretical:

What is temperature?

Yes, you heard me. Strip away the hysteria, the moral posturing, the extinction porn, and ask the most basic thing: what exactly are we measuring?

Thermometer Games

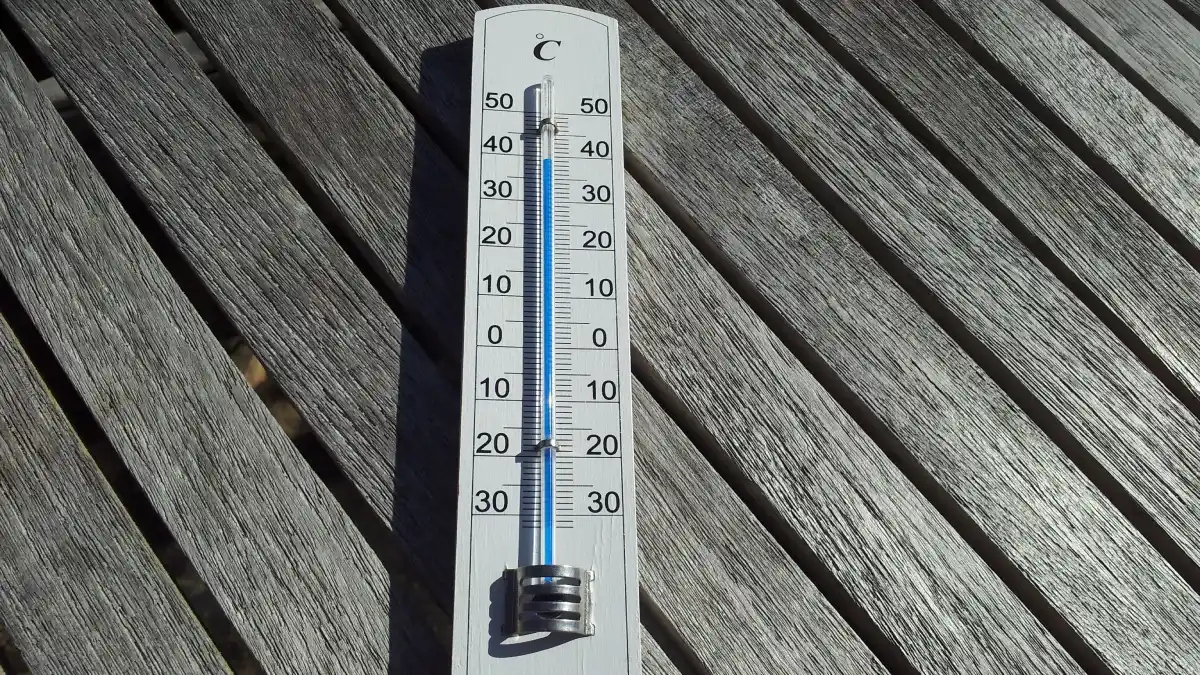

At first glance, temperature is child’s play. Glance at the thermometer, read the number, voila—the truth.

Except not.

Let’s play with this. Put one thermometer next to the exhaust pipe of an air conditioner, another beside the cooling vent, and a third in the kitchen while someone’s boiling pasta. Which one speaks for “the day’s temperature”?

Still too easy? Fine. Put one on a sunny windowsill and another by the shaded door. Do they agree? Of course not. And yet the “record-breaking heat” is supposedly pinned down to a decimal point.

Still not convinced? My apartment has ceilings 3.5 meters high (11.5 feet for the metrically challenged). Stick one thermometer on my desk and another up near the ceiling. Which one tells the truth? The air is stratified, not a monolith.

And this is all still in one room. Already, we’re swimming in contradictions.

Now record the readings every minute for an hour. Which one becomes the official temperature of the hour? The highest? The lowest? The mean? And what about the day? Multiply this circus by every room, every city, every continent, and you see where this is heading: temperature is not an absolute, it’s an agreement.

An agreement built on formulas, filters, compromises. Decisions upon decisions. Which readings to keep, which to discard, which to massage until they sing in tune with the desired narrative.

The Human Finger on the Scale

We pretend thermometers whisper neutral truths, but they don’t. They only provide raw numbers—raw numbers which must then be curated, processed, kneaded into something palatable for the charts and the talking heads.

And who decides? Humans.

Humans with careers, grants, reputations, and ideological skin in the game. Humans who, consciously or not, will favor the formula that validates their story. You don’t keep the corner office at Climate HQ by publishing “meh, pretty average week.” You keep it by feeding the beast with records, drama, and proof that the apocalypse is on schedule.

So the readings are normalized, harmonized, sanitized. Fancy words for fiddled. It’s the same old game: the data buffet is endless, and everyone piles their plates with the morsels that suit them best.

From Wilderness to Asphalt

And this isn’t even the worst of it. Imagine a thermometer, patiently taking its noon reading every day for a century. At first, it sits in open wilderness, surrounded by grass and trees. A hundred years later, it’s encircled by asphalt, office towers, exhaust fumes, and a Starbucks. Surprise, surprise—the numbers climb.

I know this because I grew up sixty kilometers north of Vienna, in a small village. Same latitude, same climate zone, different story. Snow that blanketed our village melted into gray slush in Vienna. Nights that froze us solid up north were milder in the city. Kids didn’t need thermometers to understand: the city was hotter. Always hotter.

That’s the urban heat island effect. Cities absorb heat, trap it, belch it back into the night. Pavement cooks, buildings radiate, engines spew, lights blaze. Walk barefoot one summer evening with one foot on grass and the other on asphalt—you’ll blister on one side and stay cool on the other. The Greeks knew this thousands of years ago: whitewash your houses to radiate heat. Our modern architects, in their wisdom, prefer black tarmac and glass canyons. And then act surprised when the mercury climbs.

Child’s Play with Liquid Tar

In the 1970s, summers were no gentle lullabies either. We kids scraped liquid tar from the cracks in the pavement and smeared it between our toes like war paint. We hopscotched from one patch of shade to another, our soles sizzling on the stones. Vienna was hotter than the village, and that just meant more fun.

We didn’t call it a crisis. We called it summer.

But now, grown adults stitch every disparate experience into a single “average global temperature.” A Frankenstein number cobbled together out of conflicting, incompatible, cherry-picked readings. Because nothing says “science” like turning a billion microclimates into one politically convenient statistic.

Cooking the Records

Back to today’s so-called records. Some “hottest day ever” readings were logged beside air ducts, greenhouses, even on the tarmac of parking lots. Honestly, you’d get a straighter result holding a lighter under the thermometer. At least then the fraud would be honest.

Temperature is not like gravity or the speed of light. It doesn’t exist as a universal constant. It is circumstantial. It depends on where, when, how, and why you measure it. And then it depends on what story you want to tell about it.

And the story right now is worth billions. Trillions. Whole careers, whole industries, whole bureaucracies. Once the Climate Compliance Machine became a money-printing press, human nature did what it always does: it leaned in, whispered “yes,” and found a way to game the system.

Robin Williams Would’ve Laughed

Robin Williams made us laugh at war, at the absurdity of young men frying in jungles for causes they didn’t choose. He ridiculed the unbearable by making it ridiculous.

Today, the climate-industrial complex deserves the same treatment. Because the hysteria has calcified into religion, complete with high priests, indulgences, and public penance. And if we don’t laugh, we’ll end up believing that every bead of sweat is proof of the end times.

So let’s borrow Robin’s trick. Let’s treat the “hottest day ever” not as a death knell, but as a crotch-pot cooking joke. Let’s recognize that a thermometer on a parking lot is not the voice of Gaia but the voice of bureaucracy. Let’s remember that data is never pure, never free from fingerprints, never immune to ambition.

Because humor may be the only thing that keeps us sane once we realize what swamp we’ve waded into.

Good morning, thermometer.